Current:

Michel Auder

SAVAGE MEN

November 14th 2025 - January 18th 2026

Opening: Friday, November 14th, 5 - 9 pm

(to preview, please contact the gallery here)

Savage men / male fatales

(by Natalia Sielewicz)

“He looked at me as if I were an audience, not a person,” implies the narrator of Gary Indiana’s novel Horse Crazy—a 35-year-old writer marooned in New York’s downtown art-magazine circuit, who becomes infatuated with a younger man, Gregory Burgess, a former heroin addict and part-time artist. What follows is a typical situationship ordeal: unrequited desire played out against a landscape of irony, exhaustion, and commodified feeling. The narrator accepts humiliation with the diligence of a profession—buying Gregory things, paying his rent “because it made him smile,” waiting by the phone, forgiving betrayals—and, crucially, knowing exactly what he’s doing. Indiana renders this submission almost aesthetic: the narrator dissects his own abasement even as he repeats it, a man rehearsing his downfall in perfect prose. Perhaps it isn’t naïve love; perhaps he isn’t just an audience after all. He’s a person with agency—addicted to suffering because suffering is the last thing that feels real in a world made of simulations.

In Savage Men, Michel Auder, chronicler of intimacy and its discontents, turns the same scalpel on masculinity itself. His camera exposes manhood as a scripted, over-rehearsed performance that always threatens to fail. He approaches the theme tenderly, almost conspiratorially, through two of his friends—Gary Indiana and the actor, former Warhol superstar Louis Waldon—both caught at the brink of private desperation. Each, in his way, performs despair for an audience of one: Auder’s camera and, more importantly, himself. They act out despair as if it were a form of escape, a method of puncturing the numbness that trains us to confuse hierarchy with intimacy.

The first film, Seduction of Patrick, shot at Olivier Mosset’s Broadway loft in the early 1980s, follows Indiana in his self-abasement before another younger man. Patrick could easily be Gregory’s double, except that he exists—he is real, and Gary is performing for him in real time. Around them orbit a cast of dubious love advisors: Viva, Warhol superstar, casting an ironic maternal eye over his degradation; Florence Lambert offering Gary ballet lessons as moral rescue; Marcia Resnick and Cookie Mueller dispensing affectionate but useless warnings. “But desire doesn’t make you larger,” Gary says in Horse Crazy “It makes you small, like a child begging for permission.” Humanity shrinks in the face of longing; love, when it appears, feels like mercy. Everyone around him performs authenticity. And yet Gary’s confession before Auder’s camera is no less staged than anything in Seduction of Patrick and Horse Crazy. He narrates his obsession with a mix of wit, irony, and self-awareness.

The second film, a portrait of Louis Waldon, finds Auder in quieter terrain: the home of an aging superstar of Warhol’s underground. Waldon—ex-soldier, dancer, bodybuilder—once embodied the paradox of the Factory’s “macho guy,” a hypermasculine figure refracted through the camp, voyeuristic lens of Warhol’s cinema. Here, that same body has softened into vulnerability. The idolized form carries its history like fatigue: age, nostalgia, the sediment of lost bravado. Waldon’s readiness to perform himself again—to be looked at, this time not as an object of desire but as an emblem of something gone—reveals another kind of submission to the gaze that made him. His composure and fragility blur the usual gender binaries, suggesting that masculinity, too, survives only through recognition, only by being seen. In Auder’s lens, the macho façade dissolves into something more porous: a man negotiating his own afterimage, performing endurance through humour and sincerity.

At last, Savage Men—the film that lends its title to the exhibition—trails Auder and his companion, incognito, through Lucky Cheng’s, the fabled East Village club, the first restaurant in New York City to employ waitstaff, bartenders, and performers in drag. The camera glides through the smoke and red light, observing the night’s choreography of desire and its counterfeit currencies. What unfolds is less a spectacle than a ritual: a theater of transactional intimacy, where the acts of wanting and watching converge, each feeding upon the other, until the gaze itself becomes a form of exchange. Savage Men—the name of a lap-dance troupe catering to female patrons—transforms into a signifier of dual tension: the audacity of the performer exposed under the lights, and the furtive hunger of the clandestine observer, the recursive loop of spectatorship and seduction. There is no redemption here. No masters, no saviors. We are all savage men at the mercy of one another.

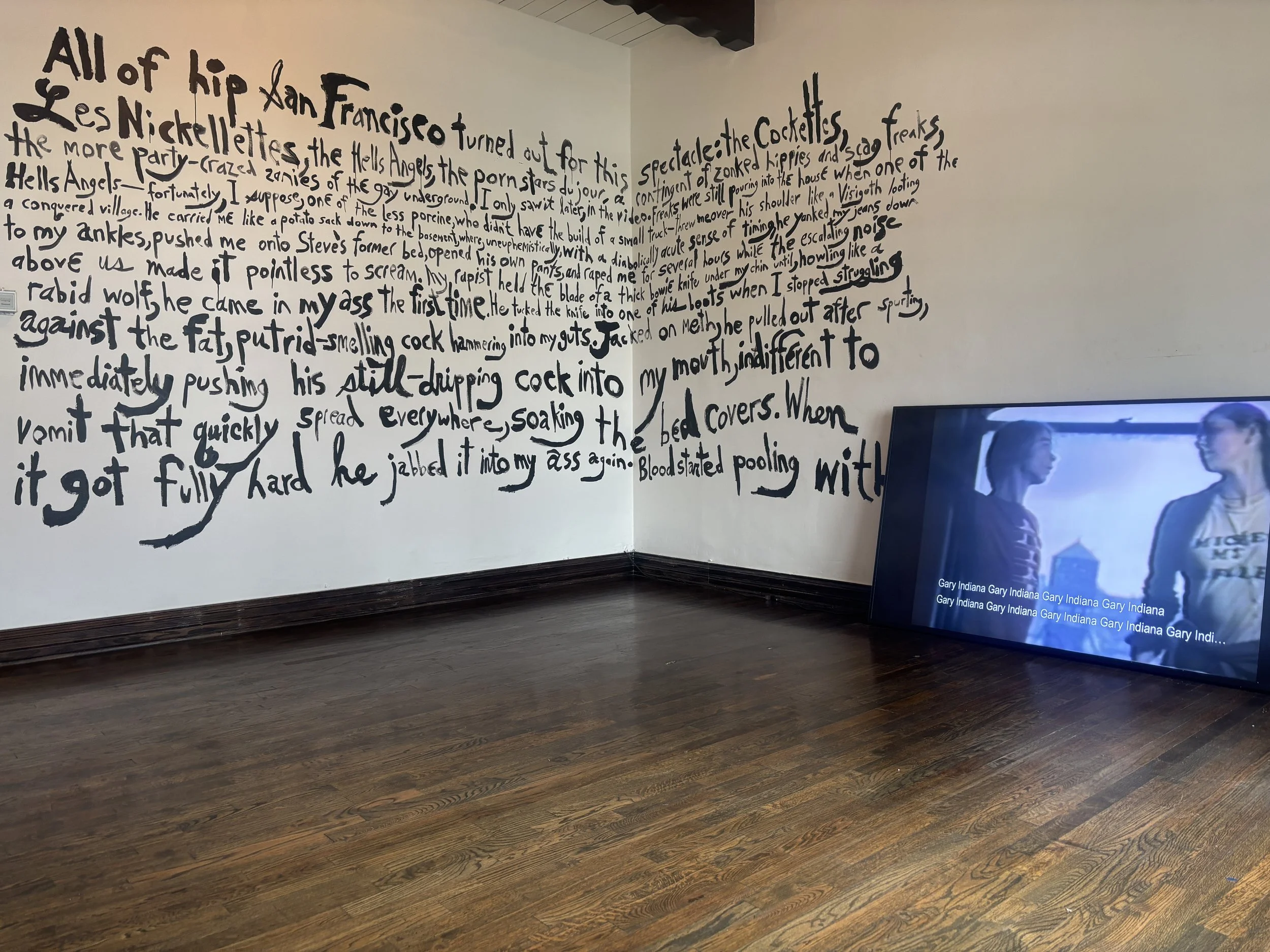

Installation view: Seduction of Patrick (1979) and mural realized together with Loren Kramar from excerpt of Gary Indiana’s book: I Can Give You Anything But Love